| Upwelling | Post-Upwelling | Winter | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Risso's dolphins | |||

| Oregon | 0.00 (1430) | 0.00 (493) | – (–) |

| Humboldt | 0.09 (489) | 0.01 (1048) | 0.03 (308) |

| San Francisco | 0.01 (960) | 0.01 (688) | – (–) |

| Morro Bay | 0.00 (2034) | 0.01 (1353) | – (–) |

| Pacific white-sided dolphins | |||

| Oregon | 0.10 (1430) | 0.11 (493) | – (–) |

| Humboldt | 0.06 (489) | 0.29 (1051) | 0.18 (308) |

| San Francisco | 0.10 (960) | 0.23 (688) | – (–) |

| Morro Bay | 0.31 (2035) | 0.12 (1353) | – (–) |

| Unidentified odontocetes | |||

| Oregon | 0.00 (1430) | 0.01 (493) | – (–) |

| Humboldt | 0.00 (489) | 0.00 (1048) | 0.00 (308) |

| San Francisco | 0.00 (960) | 0.00 (688) | – (–) |

| Morro Bay | 0.00 (2034) | 0.05 (1357) | – (–) |

Dolphins

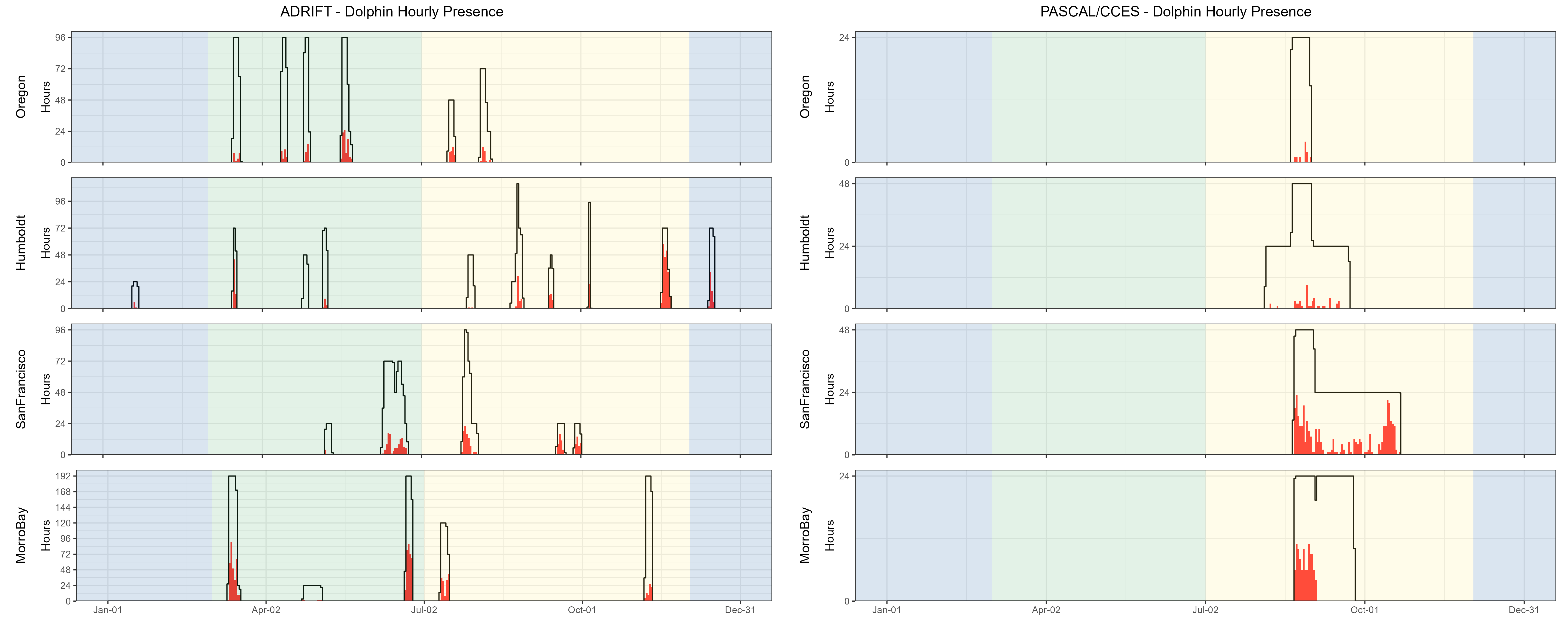

Dolphins were detected during most Adrift deployments (see table, right), as well as during the combined PASCAL and CCES survey (see table, right, and Figure 1). While dolphins were detected in all regions during the PASCAL and CCES surveys, they were more frequently detected in the San Francisco and Morro Bay regions during the Adrift study. Dolphin detections included detections that could be positively attributed to Risso’s dolphins (Gg) and Pacific white-sided Dolphins (Lo), and detections that remained unidentified (UO) (see table, right). Dolphin acoustic events attributed to Unidentified Odontocetes (UO) were uncommon relative to the number of detections of Risso’s and/or Pacific white-sided dolphins.

Dolphin schools in central and northern California are frequently encountered in large, dispersed mixed species groups (S.Rankin, pers. comm.), and here we do not distinguish mixed species from single-species groups. So, attribution of an acoustic event to Risso’s dolphins does not preclude the presence of other species. We currently lack a comprehensive acoustic classification routine that includes all dolphin schools in the region. Future research should develop a publicly available acoustic classifier for dolphins that considers mixed species groups and can be applied to different passive acoustic platforms.

There had been no visual detection of beaked whales during the 30 years of annual ACCESS surveys offshore San Francisco (J. Roletto, pers. comm.).

Previous research identified different click types for Pacific white-sided dolphins (M. Soldevilla, Wiggins, and Hildebrand 2010). The dominant click type in Adrift acoustic encounters of Pacific white-sided dolphins was ‘Type A’; however, there were some encounters with ‘Type B’. Most of these Type A encounters were at night, similar to (M. Soldevilla, Wiggins, and Hildebrand 2010), and our research identified a co-occurrence of Click Type A with goose-beaked whale (see Beaked Whales). Future research could investigate this relationship between Pacific white-sided dolphins and goose-beaked whales by taking advantage of the vertical array for separating animals echolocating at the surface and at depth. (M. Soldevilla, Wiggins, and Hildebrand 2010) suggested Type B echolocation clicks might be attributed to a nearshore population in the southern California Current (Southern California Bight and Baja Mexico); however, our results show that Click Type B can be found in other regions.

Future investigation in the geographic variation in click types for Pacific white-sided dolphins is merited.

Multiple click types have been described for Risso’s dolphins (M. S. Soldevilla et al. 2017). The dominant click type in all acoustic encounters of Risso’s dolphins in our analysis was the “Pelagic Pacific” (PPac) click type. Previous models had limited sample sizes from Risso’s dolphins in open ocean waters, and future investigations should incorporate the acoustic detections from Adrift, PASCAL, and CCES to improve the definition of geographic variation in click types throughout the North Pacific Ocean.

Opportunistic acoustic recordings were collected in the presence of dolphin groups with visually confirmed species, including single and mixed assemblages of Pacific white-sided, North Pacific right whale, Risso’s, and common dolphins. The sample sizes are currently too low to be used to develop classification models, but these recordings will be useful contributions to training datasets in the future.

Detailed methods are provided in our Adrift Analysis Methods.