| Upwelling | Post-Upwelling | Winter | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Song | |||

| Oregon | 0.03 (1430) | 0.00 (493) | – (–) |

| Humboldt | 0.13 (489) | 0.42 (1048) | 0.58 (308) |

| San Francisco | 0.03 (960) | 0.36 (688) | – (–) |

| Morro Bay | 0.40 (2034) | 0.24 (1353) | – (–) |

| Social | |||

| Oregon | 0.01 (1430) | 0.04 (493) | – (–) |

| Humboldt | 0.01 (489) | 0.16 (1048) | 0.00 (308) |

| San Francisco | 0.01 (960) | 0.24 (688) | – (–) |

| Morro Bay | 0.02 (2034) | 0.02 (1353) | – (–) |

| Unidentified | |||

| Oregon | 0.03 (1430) | 0.01 (493) | – (–) |

| Humboldt | 0.15 (489) | 0.26 (1048) | 0.18 (308) |

| San Francisco | 0.06 (960) | 0.28 (688) | – (–) |

| Morro Bay | 0.16 (2034) | 0.21 (1353) | – (–) |

Humpback Whales

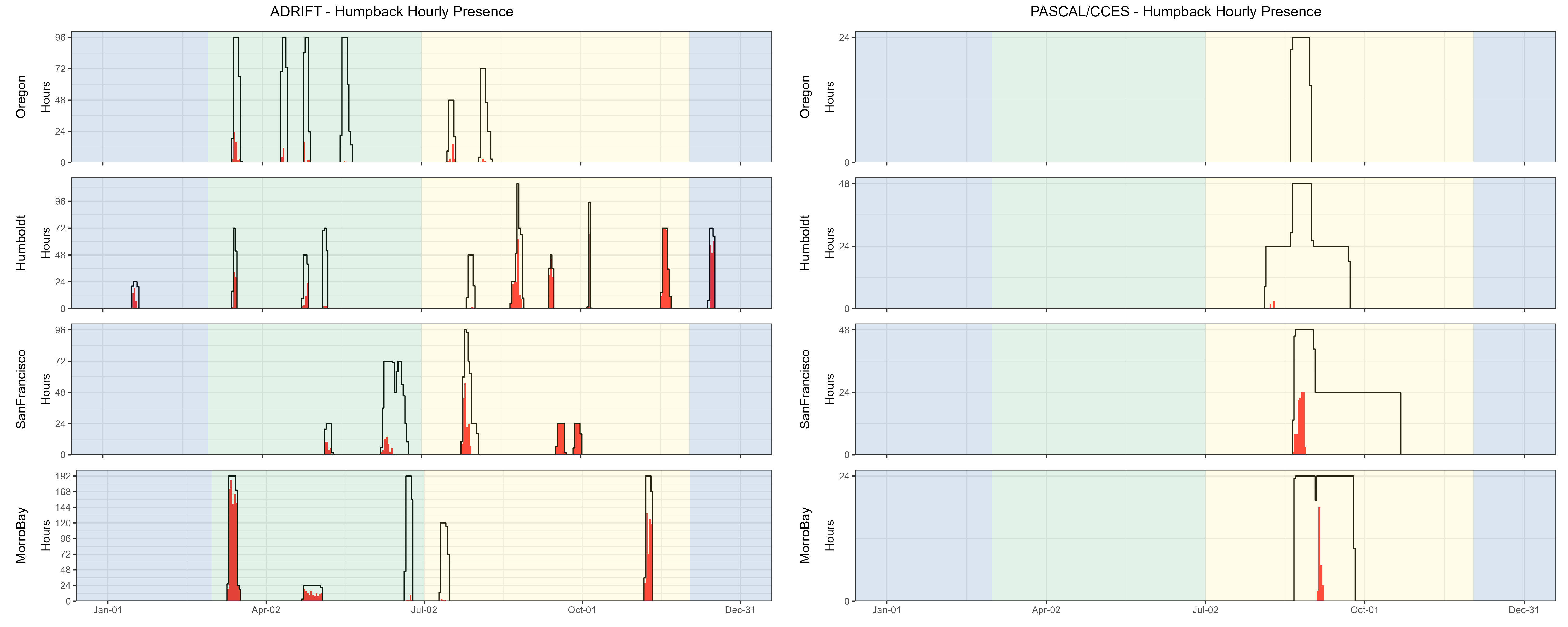

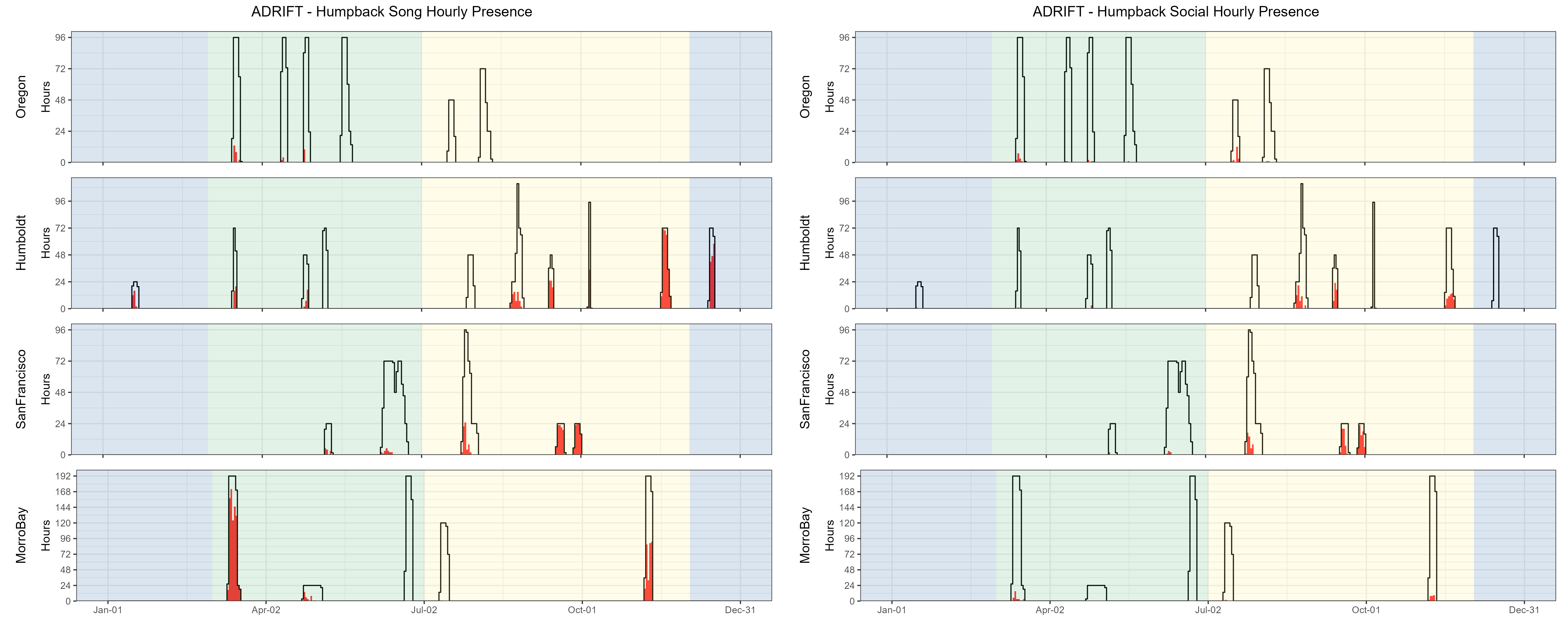

Humpback whales were detected during most deployments (Figure 1), with higher probability of detection in the post-upwelling season in Humboldt and San Francisco (see table, right). Hourly detection rates of humpback whales were lower for the combined PASCAL and CCES surveys than the Adrift study (Figure 1). Most PASCAL and CCES deployments were further offshore (west) of the Adrift study areas (see drift maps in PASCAL Expanded Datasets and CCES Expanded Datasets). Historical sighting data shows decreased distribution of humpback whales in these offshore waters (see OBIS Seamap). Humpback whales were not detected in Oregon during the PASCAL and CCES Surveys (Figure 1).

There were few acoustic detections of humpback whales during the late June/early July surveys off Morro Bay (Figure 1).

Multiple humpback whales were visually sighted during the June 2022 and July 2023 CCC surveys in Morro Bay; however, the bulk of the visual survey effort (and sightings) were south of the area acoustically surveyed. The disconnect between the visual sightings and acoustic detections could be due to local differences in the sampling areas or that the animals were not particularly vocal during this sampling period.

Hourly probability of detecting song was higher in the post-upwelling than the upwelling season for Humboldt and San Francisco, but the opposite was true for Morro Bay (see table, above). Deployments were limited in winter, but high probability of detecting humpback song aligns with the production of song during the southern winter migration (Clapham and Mattila 1990). There were several drifts in which humpback song dominated the recordings (Figure 2). The acoustic features of humpback whale song, including high source level and series of calls produced over long time spans, naturally lead to high detection rates (Au et al. 2006). While recordings dominated by song may be attributed to one or a few animals, social sounds may be attributed to larger numbers of animals (Ryan et al. 2019). There were few detections of humpback song in Oregon.

Humpback whales produce many non-song (social) calls that may be associated with feeding or social behaviors. Humpback whale social sounds most frequently detected in these analyses included the grunts, ‘wops’ and ‘thwops’ (Dunlop, Cato, and Noad 2008). We were unable to dedicate the time required to differentiate these sounds during this study. Highly annotated datasets exist, and we recommend development of machine learning models to classify humpback non-song, which may allow for an improved understanding of spatial and temporal variation in habitat use in the California Current, allowing us to identify potential critical habitat.

Detailed methods are provided in our Adrift Analysis Methods.